The traditional Mexican holiday Dia de los Muertos – or Day of the Dead – has gone mainstream in American pop culture, with its colorfully decorated skulls and flowers adorning clothing, featured in advertising, and embraced by organizations from Hollywood to major league sports. But beyond its commercial appeal, the Day of the Dead has deep roots in Hispanic culture and Catholicism.

The traditional Mexican holiday Dia de los Muertos – or Day of the Dead – has gone mainstream in American pop culture, with its colorfully decorated skulls and flowers adorning clothing, featured in advertising, and embraced by organizations from Hollywood to major league sports. But beyond its commercial appeal, the Day of the Dead has deep roots in Hispanic culture and Catholicism.

The celebration coincides with the feasts of All Saints Day and All Souls’ Day, celebrated over two to three days, usually beginning Oct. 31 and ending Nov. 2. Despite its bleak name, the Day of the Dead is not a time for mourning or for spooking friends and neighbors. It is a celebration of life – a time to honor the memory of deceased loved ones, to pray for the souls in purgatory and to ask intercession from those in heaven.

“Death … is something that comes and is certain for everyone. Instead of being frightened by it, (Catholics) see it as something natural, as a step toward heaven,” explains Father Julio Dominguez, the diocese’s vicar of Hispanic Ministry.

WHAT IS THE DAY OF THE DEAD?

The Day of the Dead is a holy feast day when families gather to pray and remember their deceased loved ones. They may visit their family members’ gravesites, spending time in prayer and beautifying the resting places with candles, flowers and personal memorabilia. They also may bring a meal that includes the favorite foods of the deceased.

It is tradition to attend Mass, and families also create altars in their homes to remember and pray for the deceased. Adorned with candles, flowers, photos and mementos, the home altar becomes the centerpiece of the celebration.

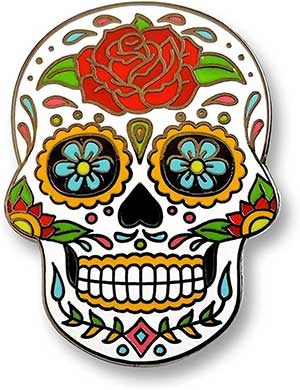

“The feast and the altar of the deceased have nothing sacrilegious or satanic about them,” says Father Dominguez, adding that the skulls popularly depicted in Day of the Dead artwork are a way of acknowledging our mortality and reminding us to aspire for eternal life with God in heaven.

On Day of the Dead home altars, Father Dominguez says, “Christ is placed on high, remembering that He is our King, and we were redeemed by Him. It is followed by images of saints, and then come the photographs of our deceased relatives, for whom we pray that they will win heaven.”

Food placed on the home altar or offered in visits to cemeteries is a custom grounded in Mexican culture, as other cultures use flowers as a sign of honor and remembrance.

“It is a practice of communion with the saints. There is something precious embodied in the traditions of the Church,” Father Dominguez says.

IT IS NOT HALLOWEEN!

The Day of the Dead is often conflated with Halloween and the folk deity Santa Muerte, but it is not connected with either.

Halloween is traditionally a solemn Christian feast day that dates as far back as the 8th century. The feast day served as a vigil in which children went house to house asking for “soul cakes” to commemorate the faithful departed. The name comes from an old Scottish term meaning “All Hallows’ Eve,” or “All Holy Night,” the vigil of the Solemnity of All Saints on Nov. 1. In the 20th century, however, Halloween devolved into a secular holiday. In recent years, confusion about the feast days has led to popular culture incorporating Day of the Dead decorations and symbols during Halloween.

“Halloween is another old tradition, but the Day of the Dead is completely different and has no common elements,” Father Dominguez says.

The wrongly named Santa Muerte (“Saint Death”), most popular in Mexico, is a folk deity personifying death, equivocal to the Grim Reaper. Santa Muerte depicts a female skeleton clad in colorful robes and wearing a crown of flowers, akin to images of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It has gained a following in popular culture, much like that of macabre movies and music in the U.S., and it has become linked to organized crime and drug trafficking. However, this folk deity and its cult following should not be confused with the Catholic celebration of the Day of the Dead. In 2016, Pope Francis and Catholic bishops of the United States and Mexico condemned all things related to Santa Muerte.

CELEBRATING THE DEARLY DEPARTED

While popular culture has distorted the feasts of All Saints Day and All Souls’ Day, the Day of the Dead is a Mexican Catholic celebration that honors one’s deceased family and friends and reminds us to pray for the dead – a spiritual work of mercy. So, whether building home altars, decorating memorials or gathering with family around the dinner table, this traditional feast is not a time of celebrating death, but a special, holy day in which we pray and remember all the deceased. Through prayer and familial communion, we look beyond death toward life’s true purpose: eternal life with God.

— SueAnn Howell

Create a home altar

Home altars are usually comprised of triangular-shaped tiers representing the three states of the Church: the living, the dead in purgatory, and the communion of saints in heaven. (Some refer to these as the “Church Militant,” the “Church Penitent,” and the “Church Triumphant.”) Follow these four steps to create your own Day of the Dead home altar:

Home altars are usually comprised of triangular-shaped tiers representing the three states of the Church: the living, the dead in purgatory, and the communion of saints in heaven. (Some refer to these as the “Church Militant,” the “Church Penitent,” and the “Church Triumphant.”) Follow these four steps to create your own Day of the Dead home altar:

STEP 1: Set up a three-tiered shelf or table in a prominent place in your home. On the top tier, prominently place a crucifix or icon of Our Lord, surrounded by images of saints or the Blessed Virgin Mary.

STEP 2: On the middle tier, place pictures or memorabilia of your deceased loved ones.

STEP 3: On the lowest tier, place favorite foods, candies or beverages of your deceased loved ones. Here, you can also place colorful skeletons or skulls made of sugar, clay or chocolate as a reminder that death is a certainty for us all, yet in this life we strive for eternal life with God in heaven.

STEP 4: Use pieces of colorful paper, representing joy, to decorate and embellish your altar. Add flowers, such as yellow marigolds which symbolize Mary, to beautify the altar. Place votive candles on all three levels, symbolizing Christ as the Light of the World. Then throughout your family’s prayers and celebrations this holiday, remember your departed loved ones.

First black saint of the Americas

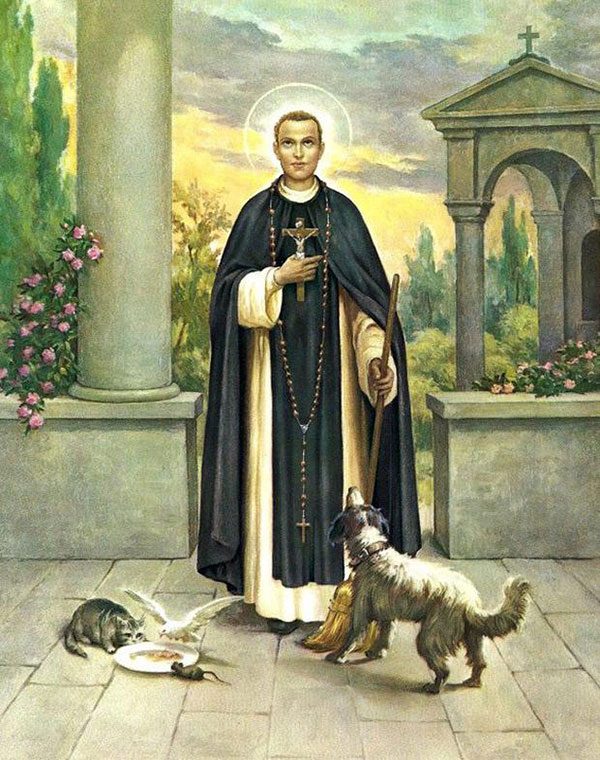

On Nov. 3 the Church celebrated the feast day of St. Martin de Porres, a Peruvian Dominican brother whose life of charity and devotion led to his canonization as the first black saint of the Americas.

On Nov. 3 the Church celebrated the feast day of St. Martin de Porres, a Peruvian Dominican brother whose life of charity and devotion led to his canonization as the first black saint of the Americas.

Martin de Porres was born in Lima, Peru, in 1579, the son of the Spanish nobleman Don Juan de Porres and the former Panamanian slave Ana Velazquez. His father at first refused to acknowledge the boy publicly as his own because Martin, like his mother, was black. Though Martin’s father later helped to provide for his education, his son faced difficulties because of his family background.

But Don Juan’s son showed great gifts at a young age. Martin served as apprentice to a doctor, and before the age of 13 he had begun to learn the practice of medicine. The young man also spent hours in prayer and practiced forms of physical mortification for the good of his soul and others.

During these years Martin had also become a member of the Dominican Third Order, which promoted the group’s spiritual practices among laypersons. He lived in their quarters and did manual work to earn room and board. But a law preventing people of mixed race from joining religious orders kept him from entering the

Dominican order as a religious brother until 1603.

Before his full admission to the order, Martin had earned the nickname of “the saint of the broom” for his diligence in cleaning the Dominicans’ quarters. After becoming a religious brother, he worked in the order’s infirmary serving the sick, a job he performed until his death.

He also had the task of begging for alms that the community would use to feed and clothe the poor. Meanwhile, he established an orphanage, as well as an orchard from which those in need could freely take a day’s supply of fruit.

Victims of medical misfortune began to suspect miracles behind some of the deeply prayerful physician’s cures. Others claimed he had appeared to them supernaturally behind locked doors or under otherwise impossible circumstances. Martin reportedly also had the gift of bilocation, and some of his contemporaries said they encountered him in places as far off as Japan even as he remained in Lima.

Others, meanwhile, marveled at his serenity and generosity.

“Many were the offices to which the servant of God, Brother Martin de Porres, attended,” testified Brother Fernando de Aragones. “Each of these jobs was enough for any one man, but alone he filled them all with great liberality, promptness and carefulness, without being weighed down by any of them.”

“It was most striking, and it made me realize that, in that he clung to God in his soul, all these things were effects of divine grace.”

Martin also loved animals. The saint refused to eat meat, and he ran a veterinary hospital for the sick creatures that seemed to seek out his help and protection.

Portrayals of the saint often include cats, dogs and even the rats to whom he showed compassion.

Many residents of Lima already spoke of Brother Martin de Porres as a living saint before his death at age 60 on Nov. 3, 1639. But his canonization did not occur until 1962, under Pope (later St.) John XXIII. He is known as a patron of interracial harmony and care for the poor.

— Catholic News Agency

St. Martin de Porres, ‘saint of the broom’

St. Martin de Porres was born in Lima, Peru, on Dec. 9, 1579 as the son of Spaniard Juan de Porres and a freed black slave from Panama, Ana Velasquez. Being of mixed race, Martin was of a lower social caste, though his father looked out for him and made sure the boy was apprenticed in a good trade.

St. Martin de Porres was born in Lima, Peru, on Dec. 9, 1579 as the son of Spaniard Juan de Porres and a freed black slave from Panama, Ana Velasquez. Being of mixed race, Martin was of a lower social caste, though his father looked out for him and made sure the boy was apprenticed in a good trade.

Martin studied to be a barber, which, at that time, meant that he also learned medicine. He became very well known for his compassion and skill as a barber, and cared for many people as well as animals.

Under Peruvian law, descendants of Africans and Native Americans were barred from becoming full members of religious orders. The only route open to the faith-filled boy was to ask the Dominicans of Holy Rosary Priory in Lima to accept him as a “donado,” a volunteer who performed menial tasks in the monastery in return for the privilege of wearing the habit and living with the religious community. At the age of 15 he asked for admission to the monastery and was received first as a servant boy, and as his duties grew he was promoted to almoner. He later took on kitchen work, laundry and cleaning. After eight years, the prior of the monastery decided to ignore the law and permitted Martin to take vows as a Third Order Dominican, which meant he was a lay man associated with the order, living at the monastery. Not everyone at the monastery accepted Martin, however, and he was verbally abused as a “mulatto dog” and mocked.

When Martin was 24, he was allowed to profess religious vows as a Dominican lay brother. He is said to have several times refused this elevation in status, which may have come about due to his father’s intervention, and he never became a priest. It is said that when his monastery was in debt, he implored them: “I am only a poor mulatto, sell me.”

Martin’s prayer life was intense, and he practiced many mortifications. He was known to levitate in ecstasy in front of the altar, but he also subjected himself to many severe penances. He was considered to be very wise, and many people sought out his advice and intercession.

He was noted for his work on behalf of the poor, establishing an orphanage and a children’s hospital. He maintained an austere lifestyle, which included fasting and abstaining from meat. Among the many miracles attributed to him besides levitation were bilocation, miraculous knowledge, instantaneous cures and an ability to communicate with animals.

He ministered without distinction to Spanish nobles and to slaves brought from Africa, curing the sick and often bringing in the sick to his own bed in the monastery when there was no room in the infirmary. One day he found a poor Indian on the street, bleeding to death from a dagger wound, and took him to his room. When he heard of this, the prior reprimanded him. Martin replied, “Forgive my error, and please instruct me, for I did not know that the precept of obedience took precedence over that of charity.” The prior gave him liberty thereafter to follow his inspirations in the exercise of mercy.

He died aged 59 on Nov. 3, 1639, and though an investigation of his life proceeded rapidly after his death, his candidacy for canonization was delayed for more than 300 years due to a series of delays, natural disasters and shipwrecks. He was finally canonized in 1962 by Pope John XXIII.

He is the patron saint of mixed-race people, barbers, innkeepers, public health workers, and all those seeking racial harmony.

— Catholic News Agency

More online

Read about more black Catholics throughout history in our special feature commemorating Black Catholic History Month in November.