All Saints' Day

All Saints' Day, Nov. 1, was instituted to honor all the saints, known and unknown, and ask for their prayers. It is a holy day of obligation.

In the early days, Christians were accustomed to solemnize the anniversary of a martyr's death for Christ at the place of martyrdom. Groups of martyrs frequently suffered on the same day, and in the persecution of Diocletian, the number of martyrs became so great that a separate day could not be assigned to each. But the Church, concerned that every martyr should be venerated, appointed a common day for all. The first trace of this was in Antioch on the Sunday after Pentecost.

Pope Gregory III (731-741) consecrated a chapel in the Basilica of St. Peter to all the saints and fixed the anniversary for Nov. 1. Pope Gregory IV (827-844) extended the celebration to the entire Church.

Many customs of the feast's vigil, Halloween, reflect the Christian belief that we mock evil because as Christians, it has no real power over us. The modern custom of "trick-or-treating" comes from the Middle Ages when poor people begged for "soul cakes" and in return prayed for departed souls.

All Souls' Day

All Souls' Day, Nov. 2, commemorates the faithful departed – those who die with God's grace and friendship.

Not everyone who dies in God's grace is immediately ready for the goodness of God and heaven, so we must be purified of the temporal effects of sin. The Church calls this purification of the elect "purgatory." Church teaching on Purgatory essentially requires belief in two realities: there will be a purification of believers prior to entering heaven, and the prayers and Masses of the faithful in some way benefit those in the state of purification.

As to the duration, place and exact nature of this purification, the Church has no official dogma, although St. Augustine and others used fire as a way to explain the nature of the purification.

― NewAdvent.org and ChurchYear.net

In November, the Church celebrates the feast day of St. Charles Borromeo, whose contributions to the Council of Trent are noteworthy. The saint also had an interesting family tree: His uncle was Pope Pius IV and his nephew was Carlo Gesualdo, a composer who became infamous as a murderer.

In November, the Church celebrates the feast day of St. Charles Borromeo, whose contributions to the Council of Trent are noteworthy. The saint also had an interesting family tree: His uncle was Pope Pius IV and his nephew was Carlo Gesualdo, a composer who became infamous as a murderer.

Gesualdo, prince of Venosa, had incredible religious figures on both sides of his family. Besides his great-uncle the pope and St. Charles Borromeo, for whom he was named, he had a paternal uncle who served as dean of the College of Cardinals and later as archbishop of Naples.

Despite these holy family relations, Gesualdo led a troubled, inglorious life. He married his cousin at a young age and, when he discovered she was being unfaithful, he surprised his wife and her lover in an amorous moment. He killed them both on the spot. A widely publicized investigation of the sordid incident determined that the killing was justified, and Gesualdo was not charged.

His second marriage was only marginally more successful. He was physically abusive and unfaithful with a mistress who was accused and convicted of witchcraft. His second wife was terribly unhappy and went to great lengths to avoid living with him. Highly unstable, Gesualdo was a masochist who hired men to stay in his vicinity and ferociously beat him several times a day.

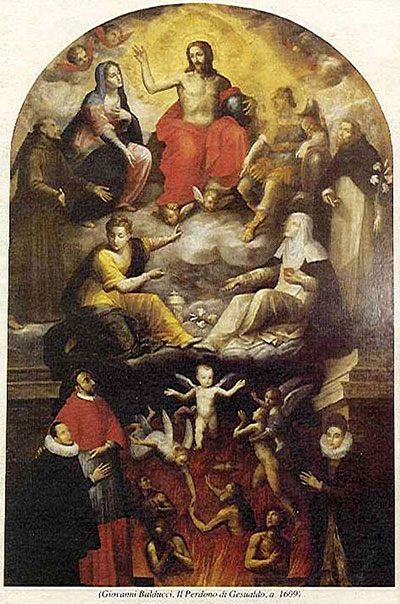

What is most interesting is his relationship to his uncle, the future St. Charles Borromeo, who was canonized in 1610. The composer died shortly afterwards in 1613, and his final wishes included a church to be built in his late uncle’s honor. Additionally, the composer commissioned a painting in 1609: “Il Perdono” (“The Pardon”), for its Santa Maria delle Grazie chapel. At the top of the painting is Christ, and counterclockwise to Him is Our Blessed Mother and St. Francis, to whom Gesualdo had a strong devotion. In the bottom left of the painting, Gesualdo kneels penitentially next to Borromeo, who is presenting him to Christ.

The fame of Gesualdo’s music lies primarily in his secular madrigals, which are extremely dissonant – so much so that nearly 200 years after they were composed, the famous English historian Charles Burney found them impossible to understand. Gesualdo also published three volumes of sacred music, all after 1600, in a style that is less dissonant than his secular music. A fine example is “O vos Omnes,” with a text from Lamentations 1:12, that Gesualdo wrote 10 years before his death in 1613. There are five voice parts – soprano, alto, tenor, quintus (or tenor II) and bass – with a scoring that focuses on the lower ranges to provide a darker sound. Also standard is the text painting with harsh intervals on “dolor” (sorrow).

Although it is only speculative, some scholars have viewed such works as “O vos Omnes” as evidence of Gesualdo’s remorse. The translation “O all ye that pass by the way, attend and see if there be any sorrow like to my sorrow” certainly gives one pause.

One may think it would be easy to become a saint if two of your uncles were archbishops and your great-uncle was a pope, yet Gesualdo shows us that holiness is not genetic.

— Christina L. Reitz, Ph.D.

More online

Listen to “O vos Omnes” by Carlo Gesualdo, the nephew of St. Charles Borromeo.