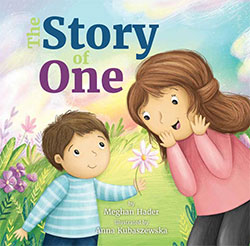

One act of kindness

A local Catholic school teacher’s experiences with generosity inspired her to pen “The Story of One,” a children’s book which illustrates just how far one small act of kindness can go. (Book cover art provided by Meghan Hader)CHARLOTTE — It took over seven years for St. Gabriel School fifth-grade teacher Meghan Hader to pen her first children’s book, “The Story of One.”

A local Catholic school teacher’s experiences with generosity inspired her to pen “The Story of One,” a children’s book which illustrates just how far one small act of kindness can go. (Book cover art provided by Meghan Hader)CHARLOTTE — It took over seven years for St. Gabriel School fifth-grade teacher Meghan Hader to pen her first children’s book, “The Story of One.”

“It started out as a poem, and then more and more stanzas and ideas came to me,” Hader says.

As with any good book, there is a story behind the story, and this book is no exception.

Hader, a native of Cincinnati, Ohio, has been teaching at St. Gabriel School for the past 14 years. She shares “Feel Good Friday” videos with her class each week that offer inspirational or funny stories highlighting a positive message.

During the 2014-’15 school year, she shared a video about a Cincinnati Bengals football player, Devon Still, whose daughter, Leah, had just been diagnosed with a rare childhood cancer.

“At the end of the video, it showed that the Cincinnati Bengals were selling Still’s jersey for $100, and all proceeds were going to the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital,” Hader recalls. “One of my students raised his hand and said, ‘I think we should get one for the class.’”

Hader says the student went to his lunch box and pulled out roughly $2. A few other students followed suit, and by the end of the day the class had about $9 toward the jersey.

“Without prompting, the students must have talked after school because the next day, over $130 showed up on my desk,” Hader recounts. “I still proudly have our class jersey displayed behind my desk from that class of 2014-’15.”

Hader believes that this simple act of giving on behalf of her students, in helping a child they would never meet, prompted her story writing.

“I just wanted to illustrate just how far one small idea can go,” she explains. “It was easy to fill in the rest of the pages (of my book) from other wonderful things I have seen through teaching, through my family, and just in everyday life.”

Hader says she doesn’t plan on a second book but hopes the universal message of doing or giving “just one” continues to carry on.

— SueAnn Howell, Senior reporter

Get a copy

Meghan Hader’s book, “The Story of One,” is available online from Amazon, Target or Warren Publishing, or in Charlotte at Park Road Books, 4139 Park Road, in the Park Road Shopping Center.

WASHINGTON, D.C. — The Catholic Mobilizing Network has introduced a new podcast, “Encounters With Dignity,” available on many popular podcast platforms.

Hosted by Caitlin Morneau, the organization’s director of restorative justice, the half-hour podcasts break down talks given during Catholic Mobilizing Network’s seminar last fall on restorative justice.

The first of the monthly installments made its premiere in January. It features Precious Blood Father David Kelly, who has been a parish-based jail minister in the Archdiocese of Chicago for the past 30 years and is one of the founders of the Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation, which focuses on three Chicago neighborhoods.

(CNS | Catholic Mobilizing Network) This is a screen grab of Catholic Mobilizing Network’s welcome message for listeners of its new podcast, “Encounters With Dignity.”In the podcast installment, he details some of his ministry. “I’ve been in courtrooms too many times,” Father Kelly said. “The focus is on punishment,” while no resources are given to those who have been harmed, he added.

(CNS | Catholic Mobilizing Network) This is a screen grab of Catholic Mobilizing Network’s welcome message for listeners of its new podcast, “Encounters With Dignity.”In the podcast installment, he details some of his ministry. “I’ve been in courtrooms too many times,” Father Kelly said. “The focus is on punishment,” while no resources are given to those who have been harmed, he added.

He recalled the 1995 heat wave in Chicago that claimed 739 lives. “One community had six times more deaths” than another in the same city, Father Kelly noted. The difference: The neighborhood with fewer deaths had a place where people could check in on one another, such as a library or community center.

So it is with troubled youths, Father Kelly said. They need, he added, “a place where we don’t say, ‘We’re just tolerating you.’”

The priest recounted an episode when he invited the Spanish-speaking mothers of murder victims to come to a prison with him to meet young men whose ages were similar to their sons. They “quickly said no,” Father Kelly said.

“But an invite to Mass – Mass they knew,” and they accepted. The Mass would be in the prison.

After Mass, there was a restorative justice circle “with jailed young people” whose “eyes were wide open,” Father Kelly said, as they heard the mothers describe their pain and heartache at the loss of children to violence.

The mothers in turn listened in wide-eyed amazement “as they heard stories of kids not knowing their mothers, families riddled with drugs,” he added.

“The moms began to lean in and see these people differently. They carried their own trauma and their own pain. They, too, were victims,” Father Kelly said. “The mothers said, ‘Well, now, what are we going to do? We can’t leave them.’ ‘Well, you can’t stay.’”

The compromise: “They insisted that they come back and bring food to these young people,” he added. “A community, albeit different, was formed.”

The second podcast, released in February, features Christina Swarns, defense attorney and executive director of the Innocence Project, and Sheryl Wilson, victim outreach specialist and executive director of the Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution.

They tell the story of how restorative approaches were used in a death penalty case that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The third episode in the series, posted this month, features Ernie Garcia, a former participant and current member of the alumni advisory committee for Rise Up Industries, an 18-month prisoner reentry program in Santee, Calif.

— Catholic News Service

More info

At www.catholicsmobilizing.org: Get more information about the “Encounters With Dignity” podcast