VATICAN CITY — Commemorating 10 years since the election of Pope Francis, the Vatican will physically represent the teachings of his encyclicals at the Venice Biennale international architecture exhibition May 20 to Nov. 26.

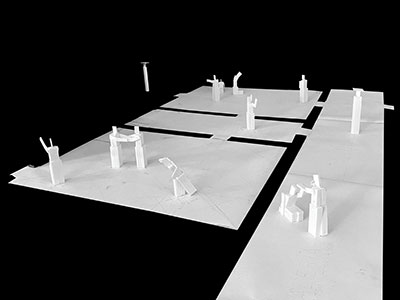

A model depicts the garden that will be part of the Holy See’s pavilion at the 2023 Venice Biennale architecture exhibition. The space is meant to represent Pope Francis’ ecological encyclical “Laudato si’, On Care for Our Common Home.” (CNS | Courtesy Studio Albori)

A model depicts the garden that will be part of the Holy See’s pavilion at the 2023 Venice Biennale architecture exhibition. The space is meant to represent Pope Francis’ ecological encyclical “Laudato si’, On Care for Our Common Home.” (CNS | Courtesy Studio Albori)

The Vatican’s exhibit, titled “Social Friendship: Meeting in the Garden,” will take visitors through scenes in which person-like “figures,” holding their arms open in welcome and acting out scenes of dialogue, convey themes inspired by the encyclical “Fratelli Tutti, on Fraternity and Social Friendship.”

The exhibit will then lead to a garden constructed of reused materials with plots growing vegetables from different parts of the world, chicken coops, seed storage facilities and rest areas. The space is intended to be one of contemplation and represent Pope Francis’ ecological encyclical “Laudato si, On Care for Our Common Home.”

Part of the exhibition will feature work by Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza, recipient of the 1992 Pritzker Prize, which is widely considered to be the highest honor in the field of architecture.

At a news conference presenting the exhibit April 18, Cardinal José Tolentino de Mendonca, prefect of the Dicastery for Culture and Education, said the Vatican’s involvement in the exhibition is an “extraordinary opportunity” since architecture is a “practical laboratory of the future, not far from typically spiritual questions.”

The Vatican’s exhibit is both an “intense political and poetic declaration about what a meeting between human beings can become,” he said, and it “puts all living things in architecture, making us all jointly responsible for our common home.”

“Over the 10 years of his pontificate, Pope Francis has acted and spoken on involving all, without forgetting the peripheries, the poor and refugees,” said Cardinal Tolentino. “This already constitutes a great legacy for the future of all those who desire a world that is more just and less wounded by social inequalities, and that is evident in the two parts of the Holy See’s pavilion.”

A model represents the figures that are part of the Holy See’s pavilion at the 2023 Venice Biennale architecture exhibition. The figures are meant to represent the teachings of Pope Francis’ encyclical “Fratelli Tutti, on Fraternity and Social Friendship.” (CNS | Courtesy Álvaro Siza) The Vatican pavilion will be assembled at the Benedictine Abbey of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, which will bring visitors “closer to the daily life of a Benedictine monastery and its Rule, opening the possibility for a renewed dialogue with those emblematic spaces of the architectural tradition,” the dicastery said in a statement.

A model represents the figures that are part of the Holy See’s pavilion at the 2023 Venice Biennale architecture exhibition. The figures are meant to represent the teachings of Pope Francis’ encyclical “Fratelli Tutti, on Fraternity and Social Friendship.” (CNS | Courtesy Álvaro Siza) The Vatican pavilion will be assembled at the Benedictine Abbey of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, which will bring visitors “closer to the daily life of a Benedictine monastery and its Rule, opening the possibility for a renewed dialogue with those emblematic spaces of the architectural tradition,” the dicastery said in a statement.

It will be the second time the Vatican has participated in the bi-yearly architecture exposition, now in its 18th edition. In 2018, it created an exhibit titled “Vatican Chapels” in which 10 architects each built small chapels, some futuristic and others rustic, in a wooded area of Venice.

— Justin McLellan, Catholic News Service

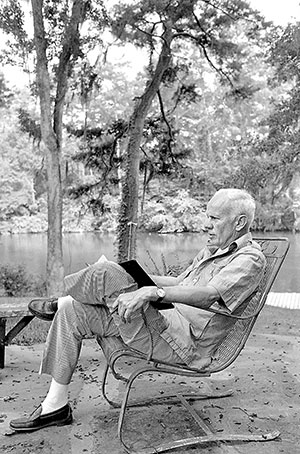

Walker Percy in his yard in Covington, La., in June 1977. (Jack Thornell | Associated Press) It is funny how one can look back at a most mundane moment and realize just how outrageously pivotal it actually was. For example, during my freshman year in college, I had a work-study job in my school’s library. With my affection for books, it seemed as though I had hit the jackpot with the best possible job. I didn’t anticipate the long stretches of boredom when we were overstaffed, combined with slow business at the circulation desk. But the librarian had a solution: reading the shelves. Idle workers were dispatched to various rooms of the library to read the shelves – that is, to look at the LC numbers and make sure the books were in order.

Walker Percy in his yard in Covington, La., in June 1977. (Jack Thornell | Associated Press) It is funny how one can look back at a most mundane moment and realize just how outrageously pivotal it actually was. For example, during my freshman year in college, I had a work-study job in my school’s library. With my affection for books, it seemed as though I had hit the jackpot with the best possible job. I didn’t anticipate the long stretches of boredom when we were overstaffed, combined with slow business at the circulation desk. But the librarian had a solution: reading the shelves. Idle workers were dispatched to various rooms of the library to read the shelves – that is, to look at the LC numbers and make sure the books were in order.

The best of all areas to be assigned was the basement, where the fiction stacks were housed. It was a playground of temptations. Read a few call numbers, straighten a few books, and succumb to the temptation to open those books that looked the least bit interesting. And if something looked particularly good, spend a few minutes perched on a stool next to the window – yes, there were windows, often open to a cool lake breeze – reading. For a freshman with the moral flexibility to read a book when she should have been reading spines, it was literary heaven.

It was during one of these moments, committing the sin of theft of wages, that I had one of the most significant and intensely educational experiences of my college career. I saw a book called “Love in the Ruins,” with the subtitle, “The Adventures of a Bad Catholic at a Time Near the End of the World.” It sounded promising. I had an intense fascination with Catholicism, and a book about a bad Catholic held promise.

“Now in these dread latter days of the old violent beloved U.S.A. and of the Christ-forgetting Christ-haunted death-dealing Western world I came to myself in a grove of young pines and the question came to me: has it happened at last?” Could anyone read this opening sentence and not be hooked? Here was a book that would not quickly be placed back on the shelf. This was one to legitimately take out and read. All the way through.

From that first reading as a callow 18-year-old Lutheran freshman of the most sophomoric pretensions, I nevertheless knew this wasn’t only a hilarious novel but something of depth. I was blessed with enough humility to remember this work and to return to it over the years, finding new depth and insight with every rereading. The book remained the same, but this reader grew and found an uncomfortable amount of present reality amid the absurdity. The world of protagonist Dr. Thomas More with his lapsometer is always funny but becoming ever more disquieting as life imitates prophetic art.

Walker Percy was born in Birmingham, Ala., in 1916 to a family of such tragedy that their despair and suicide-clouded history resembles a Southern Gothic novel. Percy’s father committed suicide when Walker was a young teen, and his mother died in a car accident shrouded in suspicion two years later. He and his two brothers were adopted by their bachelor uncle Will Percy, who raised them in the tradition of Southern manliness, scholarship and stoicism. Walker Percy’s first career was as a physician. But after being afflicted with tuberculosis while an intern in a New York hospital and taking a long, quiet recuperation that provided time for reading and thought, Percy chose to return to the South and pursue a deeper longing: the life of a writer. And it was as an adult that Percy (and his wife) converted to the Catholic Church, the faith of many of his Percy ancestors. This conversion of heart is of no small consequence; it is the spiritual essence that makes Percy’s writing more than great. The spiritual life of this man is what sets him apart from other authors who are only skilled wordsmiths and amusing storytellers.

Percy was a prolific writer, a teacher, an astute scholar in semiotics and a keen observer of life in general. It is possible to read Percy’s novels (and essays and articles and other books) with no consideration of the spirituality of the author. That is possible. But when his writings are approached in this manner – the approach I took as an ignorant freshman – so much is missed. The Christ-haunted, Christ-graced author who possessed such a superb way with words has something precious to tell us. We need only pay attention and be open to the movement of grace.

When you chat with Percy fans, there is the inevitable discussion of their favorite of his works. Some would say “The Moviegoer,” winner of the National Book Award in 1962. Others might offer “The Last Gentleman” or even the sublime, though disturbing, “Lancelot.” These are great books, deserving of thoughtful reading. But I will always say – and this is not just sentiment talking – “Love in the Ruins.” Start there. Start with “Love in the Ruins.”

Writing in 1980, the great literary scholar Dr. Ralph Wood goes so far as to say, “The novel seemed a piece of zany hyperbole when it was published in 1971. A decade later it reads like palpable prophecy.”

Ellyn von Huben is a native of Wisconsin, and has never lived more than five miles from the shores of Lake Michigan. She holds a degree in art history from Barat College in Lake Forest, Ill. This piece was originally published on Jan. 5, 2021, on WordonFire.org.