A priest forever

The story of Monsignor Joseph Showfety illustrates that a true calling to the priesthood transcends time. A priest for 65 years, he first sensed his religious vocation as a young altar server. Yet it’s easy to imagine God’s plan forming before that, outside of time as we know it – perhaps as the answer to a prayer.

The story of Monsignor Joseph Showfety illustrates that a true calling to the priesthood transcends time. A priest for 65 years, he first sensed his religious vocation as a young altar server. Yet it’s easy to imagine God’s plan forming before that, outside of time as we know it – perhaps as the answer to a prayer.

In “A Priest Is Not His Own,” Venerable Archbishop Fulton Sheen wrote, “‘Ask and the gift will come’ (Luke 11:19). Can we hope to receive if we do not ask? There are probably hundreds of thousands of vocations hanging from heaven on silken cords; prayer is the sword that cuts them. The laborers are available potentially in the heart of Christ; it is our petitions that actualize them.”

For more than 120 years, the Showfety family’s parish, St. Benedict Church in Greensboro, has been a place of profound piety and prayer. There, parishioners have continued a century-long, perpetual devotion to Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal, who has been known to bring forth religious vocations, for which the parish has become well known.

Showfety Family Legacy at St. Benedict

For nearly a century, members of the Showfety family have been like golden strands woven into the diverse tapestry of St. Benedict, shining brightly, intermingling with others, inspiring faith, fellowship, service and stewardship, all bound by an ardent love of Christ. Their roots at the parish run deep and continue to influence the life of the church today – perhaps none more so than those of Monsignor Joseph Showfety.

His parents, Abdou and Edna Showfety, were devout Catholics who fled in 1913 from an area of Syria now recognized officially as Lebanon. They came to the United States by way of Ellis Island. Abdou was 15, and Edna was 10. Accompanied by their respective relatives, they left their native country to escape harsh conditions with intentions to return after a few years to Haret Hreik, a town south of Beirut. The plan never came to fruition, and neither child ever saw their parents again. Seven years after their families settled in North Carolina, the pair were married at St. Benedict Church in Greensboro by then-pastor Benedictine Father Vincent G. Taylor, who later became abbot of Belmont Abbey.

Abdou and Edna had five children: Michel, Evelyn, Joseph, Raymond and Robert. Abdou worked long days earning a livelihood for his family as a successful businessman in Greensboro, and Edna ran the family home. Over the years, Abdou was involved with the Knights of Columbus and the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. The children attended St. Benedict School, the boys served at the altar for several years, and they all received their sacraments at the parish. Four of the five children were married at the church – all but Joseph Showfety, whose life took a different turn.

Early Life in the Parish

Born on Jan. 5, 1927, part of America’s “greatest generation,” Monsignor Showfety’s earliest memories of St. Benedict Church are of the 1930s when he learned to serve Mass in the third grade.

“The sisters who taught us in school taught us to serve Mass – every day for three weeks. After school they took us, and we had to learn all the prayers and all the responses in Latin. We had to memorize them, and we couldn’t use any kind of help. After that, we served Mass. You knew it by heart or you didn’t serve. So, I learned the Latin. Daily Mass in those days was upstairs in the convent. The school was downstairs. Very few went to daily Mass in those days,” Monsignor Showfety recalls.

He served the 7 a.m. Mass nearly every day. The Showfety family home was on Chestnut Street very close to the church. “In those days, you went under the underpass and just beyond it was a left turn and just beyond that was Chestnut Street. I’d go across the railroad tracks, cut across there, and go home after Mass, have breakfast, and go back to school.”

Soon the young Joseph Showfety was serving two Masses before school, now being held in the church. This was often the case when Abbot Taylor visited his sisters Lucy and Mary, who was blind.

“Lucy and Mary came in together always. I think Lucy drove,” Monsignor Showfety remembers keenly. “She’d come in with her sister on her arm and sit in one of the front pews for Mass. When their brother came, priests then couldn’t concelebrate. I can’t count the number of times I had to serve two Masses in the morning (before school). Each Mass was individual, and only a few of us served because of the distance involved. I was only four blocks away.”

Monsignor Showfety first felt his calling to be a priest at this early age. “Serving the Mass itself you knew,” he says. “My mother would get up and feed me. I could walk or run to the church at 7. In those days, it was no problem. Thank God.” Yet there wasn’t pressure from his parents to serve. “I wanted to do it myself,” he said.

From kindergarten to eighth grade at St. Benedict School, Monsignor Showfety remembers there weren’t many extras, noting that he and his friends would get pretty creative with their activities, especially basketball.

“We used to do things ourselves. We had no playground,” he says. “We used to use the seats of the swings. The seat was the basket. We had our own team from the school. The boys who went to public school, we would play against them and we knew them. We did pretty well for ourselves, having practiced with swings as hoops.”

Setting Course for Religious Life

So indelibly written on his heart, the priesthood was never far from view for Monsignor Showfety. The Daughters of Charity who ran the school could sense it, too. His classmates, on the other hand, could not. The sisters admonished the girls, telling them not to flirt with Joseph Showfety – he was reserved for the priesthood.

So indelibly written on his heart, the priesthood was never far from view for Monsignor Showfety. The Daughters of Charity who ran the school could sense it, too. His classmates, on the other hand, could not. The sisters admonished the girls, telling them not to flirt with Joseph Showfety – he was reserved for the priesthood.

In a 2018 interview, Monsignor Showfety recalled a similar story: “I remember the eighth grade, we had our graduation ceremony and dinner, where we read the class prophecy. One sister, God rest her, taught me four of eight grades at St. Benedict’s. I was reading the class prophecy, and they had me as a merchant having a department store in Jefferson Square because of my father, God rest him. The sister made them change it to say, ‘He’s going to be a priest.’ Sixty-three years later, you know who won,” he said with a grin.

After graduating from St. Benedict, Monsignor Showfety went to Greensboro High School (now Grimsley), where his focus shifted a bit. He became something of a local baseball star and worked at his father’s shop. But he remained close to the Church.

He recalled pitching and playing outfield for his high school team. Their games were chronicled by Smith Barrier, sports editor for the Greensboro Daily News, as well as Irwin Smallwood who wrote for his high school newspaper at the time.

Soon, the young men of St. Benedict began getting drafted into World War II, when the church also served as a place of worship and respite for soldiers from the North on weekend leave from maneuvers at North Carolina bases.

During the final months of World War II, the young Showfety attended The Citadel in Charleston, S.C., and then went on to serve 16 months in the U.S. Navy.

“My dad – this happened so quickly – he said, ‘Why don’t you go to The Citadel in Charleston?’ I think I stayed until the first of March or so and went into service from there,” he recalls. “There were no deferments back in those days. The time came and you went, and that was that. You were drafted, and that’s all there was to it.”

After his military service ended, another kind of service began – drafted by God for the priesthood long ago. The young Showfety started his studies at Mount Saint Mary’s College (now University) in Emmitsburg, Md., attending there for four years. Bishop Vincent Waters of Raleigh then transferred him to St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore, the nation’s oldest Catholic seminary, to complete his studies for the priesthood.

On May 19, 1955, at the age of 28, St. Benedict’s native son became a Father. He was ordained with Father Thomas Clements and Father Robert Shea at Sacred Heart Cathedral in Raleigh, then served his first Low Mass at his home church St. Benedict the next day and his first Solemn High Mass at Our Lady of Grace Church in Greensboro on May 22.

Monsignor Showfety credits Daughter of Charity Sister Genevieve Riordan, his other teachers from the order, and Monsignor Hugh Dolan, pastor, for encouraging his vocation. He noted that two other “old-timers” at St. Benedict became priests: Father Thomas Berry, a Passionist, and Father John Wall of Raleigh.

His first assignment was Our Lady of Guadalupe Church in Newton Grove, where a church for black Catholics and a church for white Catholics on the same block were served by the same priests and nuns. The diocese ordered the two churches to integrate, and some parishioners left. Having grown up at a church that had welcomed black Catholics since its construction in 1899, seeing a segregated church was not a pleasant sight for the young priest.

In 1959, just four years after his ordination, Father Showfety helped open Bishop McGuinness High School, where he taught three classes a day in addition to his administrative and spiritual roles as the school’s first director.

The Birth of a Diocese

Monsignor Showfety was one of the first to learn in late 1971 when Raleigh Bishop Vincent Waters told Monsignor Michael Begley that he had petitioned Rome to divide his diocese of 60,000 Catholics and create the Diocese of Charlotte. Father Showfety gives his first priestly blessing to his parents, Abdou and Edna Showfety. (File and provided photos)Big news came four years after Father Showfety had moved on from his role at the high school.

Monsignor Showfety was one of the first to learn in late 1971 when Raleigh Bishop Vincent Waters told Monsignor Michael Begley that he had petitioned Rome to divide his diocese of 60,000 Catholics and create the Diocese of Charlotte. Father Showfety gives his first priestly blessing to his parents, Abdou and Edna Showfety. (File and provided photos)Big news came four years after Father Showfety had moved on from his role at the high school.

He was one of the first to learn in late 1971 when Raleigh Bishop Vincent Waters told Monsignor Michael Begley that he had petitioned Rome to divide his diocese of 60,000 Catholics and create the Dicese of Charlotte.

Just before Thanksgiving 1971, Bishop Waters visited Monsignor Begley in Greensboro, then pastor of Our Lady of Grace Church. Under the guise of looking for property in Greensboro for future parish use, Bishop Waters took the pastor with him. The Raleigh diocese already owned property nearby to relocate Notre Dame High School. Bishop Waters drove onto the property, stopped his car and turned to Monsignor Begley, saying, “Rome has decided to have a second diocese in Charlotte with you as the first bishop. Will you accept?” The answer was yes. Bishop Waters restarted his car without saying another word.

At the time of the division, Charlotte had 34,000 Catholics. And none of them – priest or laypeople – had any idea of the impending news. The Friday after Thanksgiving, just days after that car ride with Bishop Waters, Monsignor Begley traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet the apostolic delegate. The following Tuesday, the news about the Charlotte diocese was announced.

So how did Monsignor Showfety become the Charlotte diocese’s first chancellor?

He remembers the day well. He was serving as pastor at Immaculate Conception Church in Hendersonville at the time, and there had been a freak snowstorm. He had just come back to the rectory from shoveling a path to the church through 15 inches of snow. It was a First Friday, Dec. 3, 1971, and he needed to prepare to celebrate 11 a.m. Mass. The phone rang.

“It was Bishop-elect Begley calling. I congratulated him and our conversation continued. He said, ‘I want you to be chancellor.’ My reply was, ‘I want to build a new church in Hendersonville.’ He replied, ‘I know you do. It’ll be built, but not by you. I want you in Charlotte.’”

For the next few weeks, Monsignor Showfety traveled back and forth several times to Raleigh and worked with the chancellor there, Monsignor Louis Morton, on arrangements for setting up the new diocese. It was the holiday season, but they had only six weeks to set everything up. The date for Bishop Begley’s ordination had been set for Jan. 12, 1972, at St. Patrick Cathedral, which was being elevated from its status as a parish church.

Titles for all parish properties and all diocesan vehicles had to be transferred from Bishop Waters to Bishop Begley. It was quite a lot to do for the six men involved: two bishops, two chancellors, and two attorneys. Monsignor Showfety spent three days just transferring car titles at the state Department of Motor Vehicles in Raleigh.

“Everything was in Bishop Begley’s name as Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charlotte and his successors in office,” making the bishop “one of the largest landholders in the state,” he notes.

That excitement and rapid pace set the tone for the new diocese and Monsignor Showfety’s role as chancellor, yet, he adds, “everything fit in place.”

He recalls that from the beginning, Bishop Waters strove to divide the dioceses’ assets equally and with fairness to everyone involved. It was a critical leadership decision that placed both dioceses on good working terms from the start – something not always seen in other dioceses.

Clergy throughout North Carolina were “frozen” in place through the 1971-’72 split, and all property and funds where possible were divided equally.

“I can’t say enough about Bishop Waters,” Monsignor Showfety says. “He was a man who worked and worked and worked – extremely hard – and he traveled this diocese for almost 30 years, east to west. He knew the priests; he knew the parishes.”

Monsignor’s Chancellorship

In October 1977, Monsignor Showfety returned to St. Benedict as chancellor to celebrate the centennial of his home parish. There, he announced that St. Benedict had produced “more priests, nuns and missionaries than any other parish in the state,” the Greensboro Daily News reported. At the time, the parish counted 11 vocations: three priests, and eight religious sisters. There have been many more since.

One of the last projects Monsignor Showfety was involved in as chancellor was renovating St. Patrick Cathedral in 1979 to accommodate the reforms of Vatican II.

Some earlier plans had included a proposal to replace the pews with folding chairs and the altar with a portable altar that could be moved to different places in the church, but that proposal was summarily rejected. Instead, Monsignor Showfety hired Francis Gibbons of Baltimore, who was known for church renovations and also later did work at St. Leo Church in Winston-Salem.

The marble altar was reworked, a new pipe organ was installed, and the ceiling was redesigned. Over the nave, a blue and silver ceiling was painted depicting crowns with a cross along with wheat and grapes, symbols for the Eucharist. The design comes from the diocesan coat of arms and serves as a reminder of Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg, for whom the city of Charlotte is named.

Among the many firsts Monsignor Showfety was a part of was being the first of four monsignors appointed by the new diocese in 1976. (The three others were Monsignors William Pharr, Richard Allen and Michael O’Keefe.)

The honor was meant to be a surprise, but that day – as on most days – he was the one to open the mail at the diocese’s offices. He couldn’t help but see the confirmation letter from Rome, he recalls with a laugh, and he had to feign surprise when Bishop Begley made the announcement later that afternoon.

Of all the changes over the years, Monsignor Showfety is proud of how the diocese has grown and flourished, and he applauds the growing participation of the laity and an emphasis on stewardship.

He notes, “It was the biggest honor and privilege of my priesthood” to serve as the diocese’s first chancellor.

That particular role ended in 1979. During his ministry before and after his chancellorship, he served 11 parishes and two schools in the diocese, often overseeing new building projects and renovations, including projects at his first and last parish assignment.

Going Home Again

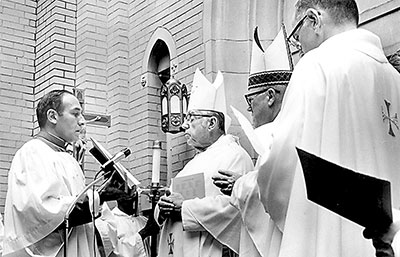

Father Showfety and fellow Charlotte jubilarian Father Thomas Clements on their ordination day, with fellow ordinand Father Robert Shea and Bishop Waters.In 1993, Monsignor Showfety returned to his beloved St. Benedict as pastor. The church had fallen into disrepair, and needed both physical and financial help. The steeples were crumbling, the roof leaked, and the bricks were loose and grimy after decades bearing the elements. Greensboro Catholics could attend Masses at newer and bigger churches in town, and the fact that St. Benedict had a reputation for being old and stodgy didn’t help. However, Monsignor Showfety had a few ideas – the building was repaired, the bricks were cleaned and restored, the finances were shored up, and the downtown parish rebounded.

Father Showfety and fellow Charlotte jubilarian Father Thomas Clements on their ordination day, with fellow ordinand Father Robert Shea and Bishop Waters.In 1993, Monsignor Showfety returned to his beloved St. Benedict as pastor. The church had fallen into disrepair, and needed both physical and financial help. The steeples were crumbling, the roof leaked, and the bricks were loose and grimy after decades bearing the elements. Greensboro Catholics could attend Masses at newer and bigger churches in town, and the fact that St. Benedict had a reputation for being old and stodgy didn’t help. However, Monsignor Showfety had a few ideas – the building was repaired, the bricks were cleaned and restored, the finances were shored up, and the downtown parish rebounded.

When he arrived as pastor, there were only 100 families, and just three years later, the number had grown by 50 percent. In 2000, he opened a new parish life center, requesting that it be dedicated to his parents who so loved the parish – his mother Edna having made a $100,000 donation to help build the center.

Moving with the times while rooted in authentic Catholic teaching, Monsignor Showfety shepherded God’s people throughout his years of ministry. He had a clear vision for how things should be done at the parish, and showing reverence to God and His Church was chief among them.

His concern for the St. Benedict Parish community was obvious, and many parishioners remember him for his loving and compassionate counsel in confession. His spirituality also greatly influenced St. Ben-edict’s stated mission today.

After nearly 50 years serving the diocese, he retired in 2002 and moved into an apartment that was once his mother’s. Later, he moved to Maryfield Nursing Home at Pennybyrn in High Point. Since his retirement, he has returned to St. Benedict for several joyous occasions, including a celebratory Mass for the 60th anniversary of his ordination.

On Sept. 22, 2017, he returned once again – this time to concelebrate Mass and the dedication of a new altar by Bishop Peter Jugis. The interior of the church had been restored to the way it looked when Monsignor Showfety served daily Mass as a boy more than 80 years prior.

During the celebration in the parish hall he built, Monsignor Showfety posed for a photo with Bishop Jugis and the current and former St. Benedict pastors. He enjoyed looking at the display of historical photographs of the church, some from his altar-serving days in the 1930s. Though he was retired dur-ing this particular restoration, the parish’s planning was heavily inspired by the “Monsignor Showfety way.”

The longtime priest’s legacy was chronicled in a book released early this year called “Pioneering Spirit: The History of St. Benedict Catholic Church From Inception to Restoration.” When presented with the book, Monsignor Showfety pored through the pages for quite some time, remarking on the goodness and holiness of the priests and bishops in the photos while marveling at newspaper clippings of the wartime Masses at St. Benedict and his parents’ wedding announcement. In his eyes, one could see how deeply he has loved being a priest these 65 years. His example coupled with God’s grace is sure to inspire faith, love, service and priestly vocations for generations to come.

— Annie Ferguson, Correspondent