From Pilgrims to priests

On Nov. 11, 1620, a group of Protestants fleeing religious persecution in England landed at Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts. Four hundred years later, three of their descendants are serving together in the Diocese of Charlotte.

On Nov. 11, 1620, a group of Protestants fleeing religious persecution in England landed at Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts. Four hundred years later, three of their descendants are serving together in the Diocese of Charlotte.

The irony of history isn’t lost on the three clergy: Monsignor Patrick J. Winslow, diocesan vicar general and chancellor; Father W. Becket Soule, pastor of St. Margaret of Scotland Parish in Maggie Valley; and Father Christian Goduti. They are directly descended from the Pilgrims, who were anti-Catholic – their families bound together by history and faith following that voyage 400 years ago.

Now, there are new discoveries in their connections to the Mayflower, the famous ship that transported more than 100 English men, women and children – collectively known today as the Pilgrims – from Plymouth, England, to the New World.

Among the discoveries:

Msgr. Winslow

Msgr. Winslow Father Soule

Father Soule  Father Goduti • Monsignor Winslow recently learned he has a third connection to the Mayflower, deepening his family’s ties to the iconic voyage. One of them is Edward Winslow, the man who wrote down the story of the first Thanksgiving – one of the only known accounts of the gathering that became American lore.

Father Goduti • Monsignor Winslow recently learned he has a third connection to the Mayflower, deepening his family’s ties to the iconic voyage. One of them is Edward Winslow, the man who wrote down the story of the first Thanksgiving – one of the only known accounts of the gathering that became American lore.

• Father Soule recently took the helm as Governor of the Society of Mayflower Descendants in North Carolina. The Pilgrims’ religious courage continues to inspire him.

• And Father Christian Goduti is unearthing his own connections to the Mayflower, with bloodlines dating back to two Pilgrim families who showed tenacity and courage – including giving birth aboard the Mayflower – to build lives of freedom in a new land.

“Thanksgiving was sort of ‘our holiday,’” Father Soule says, recalling family gatherings during his childhood. “The kind of connection (for us) was different than what you get in the school books. It was a personal connection, not just a story.”

“Reflecting upon the fact that I had relatives, including an ancestor, on the Mayflower adds a personal layer to our shared national history we celebrate on Thanksgiving,” Monsignor Winslow says.

“And something in me enjoys the irony of my family’s gravitation back to the Catholic faith from ancestors who fled to get away from the Church of England and lingering Catholic influence. From their perspective now, I think they are pleased that some of their descendants are serving God and the Church as priests. The full light of God has a way of changing one’s perspective.”

Thanksgiving is ‘a personal connection, not just a story.’

— Father W. Becket Soule

The Pilgrims’ Escape

“The Mayflower Compact 1620,” an 1899 painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, depicts John Alden signing the document. Alden is one of the Pilgrim ancestors of Father Christian Goduti.On its voyage to the New World in 1620, the Mayflower carried 102 people: “Separatists” seeking religious freedom, non-Separatists recruited by London merchants to help establish the colony, indentured servants and apprentices, and sailors contracted to stay for a year in “New Plymouth.”

“The Mayflower Compact 1620,” an 1899 painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, depicts John Alden signing the document. Alden is one of the Pilgrim ancestors of Father Christian Goduti.On its voyage to the New World in 1620, the Mayflower carried 102 people: “Separatists” seeking religious freedom, non-Separatists recruited by London merchants to help establish the colony, indentured servants and apprentices, and sailors contracted to stay for a year in “New Plymouth.”

After unexpected delays, the ship set sail across the Atlantic in September, the middle of storm season. With cramped quarters and rough seas, the miserable journey took two months and ended in present-day Massachusetts – hundreds of miles away from the Pilgrims’ intended target of Virginia, where England had already established its first successful colony at Jamestown.

The voyage culminated in the signing of the Mayflower Compact, which established a rudimentary form of democracy, with each member of the new community contributing to its welfare.

Many of the Pilgrims were virulently anti-Catholic. Even the Church of England – which had split from the Catholic Church a hundred years earlier – was still too Catholic for the “Separatists,” a Puritan faction that ascribed to the English Separatist Church.

But not all were seeking a separation from the Church of England. Some were simply seeking a new life and were skilled workers, farmers, merchants and soldiers who played vital roles in the success of the voyage and the new settlement.

Thanksgiving for survival

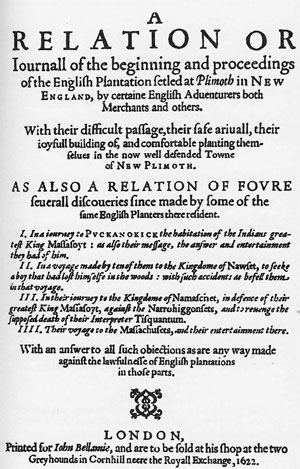

The frontispiece of “Mourt's Relation,” published in London in 1622We commonly trace the Thanksgiving holiday to the 1621 celebration at the Plymouth colony, where the Plymouth settlers held a harvest feast after a successful growing season. But the celebration was about more than food – it was about gratitude for their survival: half of the original Pilgrims had died during their first winter in Plymouth, and the colony was on the brink of failure.

The frontispiece of “Mourt's Relation,” published in London in 1622We commonly trace the Thanksgiving holiday to the 1621 celebration at the Plymouth colony, where the Plymouth settlers held a harvest feast after a successful growing season. But the celebration was about more than food – it was about gratitude for their survival: half of the original Pilgrims had died during their first winter in Plymouth, and the colony was on the brink of failure.

Squanto, a Patuxet Native American who lived among the Wampanoag tribe, taught the Pilgrims how to catch eel and grow corn and served as an interpreter for them. Another quirk of history: Squanto had learned to speak English while living in England, where he had worked after being freed by Franciscan priests from his Spanish slave owners and thenconverted to Catholicism.

Thanks to this unlikely Catholic, the anti-Catholic Pilgrims were able to survive and eventually thrive.

The Pilgrims celebrated at Plymouth for three days after their first harvest in 1621. It included approximately 50 Pilgrim survivors and 90 Native American guests.

The feast was cooked by the four adult Pilgrim women who survived that first harsh winter in the New World, including one of Monsignor Winslow’s distant aunts, Susanna (White) Winslow.

Edward Winslow, who penned “Mourt’s Relation,” one of only two eyewitness accounts of that first Thanksgiving:

“Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruits of our labor. They four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which we brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain and others. And although it be not always so plentiful as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.”

Winslows on the Mayflower

3. A portrait of Edward Winslow, the only Pilgrim to have a verified portrait, painted in 1651 in London. It now hangs in the Pilgrim Museum in Plymouth, Massachusetts.Monsignor Winslow traces his lineage back to four Pilgrim Fathers – one of whom he only recently discovered with the help of Father Soule’s research.

3. A portrait of Edward Winslow, the only Pilgrim to have a verified portrait, painted in 1651 in London. It now hangs in the Pilgrim Museum in Plymouth, Massachusetts.Monsignor Winslow traces his lineage back to four Pilgrim Fathers – one of whom he only recently discovered with the help of Father Soule’s research.

Father Winslow’s great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-uncles are Edward and Gilbert Winslow, who arrived on that first voyage from England in 1620.

Edward Winslow was just 25 and brother Gilbert was only 20 when they boarded the Mayflower and set out for the New World. Both signed the Mayflower Compact.

Edward and Gilbert’s 30-year-old brother Kenelm – Monsignor Winslow’s great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather – followed them to Plymouth on a second Mayflower ship that landed on May 16, 1629, with 35 passengers.

Monsignor Winslow remembers hearing his father retell stories about their family’s heritage that were passed down from his grandfather Chester, who was born in 1891.

“What I remember as a child was a story my grandfather told my father,” he recalls. “He related to my father and my aunt about the Winslow brothers on the Mayflower. We never focused on it, but it was brought up occasionally.

“I also heard that my aunt, who lived in Boston, took her children one year to see a display on the Pilgrims on the Mayflower. There was information on the three Winslow brothers. I grew up as one of three Winslow brothers, so that is kind of funny.”

Edward Winslow later became the third governor of the Plymouth colony, serving from 1633 to 1634. He did not stay in Plymouth, though. In 1646 he traveled to England to serve the

Puritan government of Oliver Cromwell, and never returned. In 1655 he died of fever while on a British naval expedition against the Spanish in the Caribbean and was buried at sea.

Eyewitness to Thanksgiving

Edward Winslow is partly to thank for our knowledge of the Pilgrims in America. He was the author of several important pamphlets, including “Good Newes from New England,” and he co-wrote with William Bradford the historic “Mourt’s Relation,” published in 1622.

Edward’s brother Kenelm Winslow purchased several land grants, later becoming one of the 26 founding proprietors of Assonet (now Freetown), Mass. He held various town offices, including deputy to the general court, and early court records show he had considerable litigation experience. He died in Salem, Mass., on Sept. 13, 1672.

Another depiction of the First ThanksgivingLike his ancestor more than 350 years ago, Monsignor Winslow has also served as a lawyer – a canon, or Church, lawyer.

Another depiction of the First ThanksgivingLike his ancestor more than 350 years ago, Monsignor Winslow has also served as a lawyer – a canon, or Church, lawyer.

Originally from upstate New York, Monsignor Winslow was ordained in 1999 in Albany, N.Y., and transferred to the Charlotte diocese in 2002. Bishop Peter Jugis appointed him vicar general and chancellor of the diocese in 2019.

“My grandfather, Chester, was not Catholic. So he would have been part of the tradition of those who had come over on the Mayflower. But my grandmother, Margaret, was Catholic.

My father and his sister were raised Catholic in Albany,” he says.

Monsignor Winslow reflects it is an ironic twist of history that the Winslow Pilgrims, who were once so anti-Catholic that they even shunned the Anglican Church, would have a Catholic priest among their direct descendants.

And just this year, Monsignor Winslow learned from his fellow Charlotte priest – Father Soule – that yet another direct line to the Pilgrims exists. Separatist Thomas Rogers, traveling with his 17-year-old son, arrived on the original Mayflower in 1620. His wife and other children would travel to the New World sometime later, and Monsignor Winslow’s great-grandfather (Chester’s dad) married Sarah Rogers, herself a direct descendant of Thomas Rogers.

Thomas Rogers was one of the signers of the Mayflower Compact, but died in late 1620 or early 1621 during the first wave of illness the colony endured during its first winter.

Soule’s life of service

George Soule's gravestone in Duxbury within the Myles Standish Burial GroundFather Soule’s great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, George Soule, was an indentured servant to Monsignor Winslow’s ancestor Edward Winslow.

George Soule's gravestone in Duxbury within the Myles Standish Burial GroundFather Soule’s great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, George Soule, was an indentured servant to Monsignor Winslow’s ancestor Edward Winslow.

The young George Soule came over on the Mayflower in 1620 and was among those who signed the Mayflower Compact. Released from his indenture after a couple of years, he married Mary Beckett in 1625 at Plymouth and they had nine children, seven of whom survived well into adulthood.

He and his family moved to nearby Duxbury, Massachusetts, very early on, and he was a deputy to the Plymouth Court for a number of years beginning in 1642. He volunteered for the Pequot War of 1637, but Plymouth’s troops were not needed. He served on various committees, juries and survey teams during his life in Duxbury.

Besides George Soule, Father Soule is descended from several other passengers of the Mayflower: Isaac Allerton, John Alden, William Bradford, Francis Eaton, Samuel Fuller,

Edward Fuller, John Howland and Richard Warren, as well as Philip Delano of the Fortune who arrived in 1621.

“In my family, the Mayflower was such a presence,” Father Soule says. “We knew we were descended of the Mayflower growing up, certainly from George Soule.”

The Pilgrims’ religious fervor is a point not lost on Father Soule.

“They thought they were supposed to live according to the Gospel,” he says. “It’s more than simply worship. They organized the colony on Biblical principles, following the Acts of the Apostles.

“This was in order to live the Gospel, for lack of a better term, in an ‘intentional community.’ ... That’s why they initially held everything in common.”

Father Soule’s own faith journey has led him back to Catholicism.

He grew up in Huntersville and earned degrees from Davidson College, Episcopal Divinity School, the University of Dallas and Harvard University, as well as a professional

Certificate in Genealogical Research from Boston University.

Originally ordained an Episcopal priest, he converted to Catholicism in 1988 and joined the Dominican order.

“I moved a lot (over the course of time) and a lot of my work now is involved in genealogy and various groups,” he notes.

He has taught at the Catholic University of America, the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C., the Pontifical College Josephinum in Columbus, Ohio, and Oxford University. Besides serving the parish in Maggie Valley, he is emeritus professor of canon law at Saint Paul University in Ottawa, Ontario.

Father Soule now serves as governor of the Society of Mayflower Descendants in North Carolina, which will celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2024. With more than 400 members, the Mayflower Society is open to anyone able to prove they descend from the 23 original families of the Mayflower.

“I have become very active in the Society of Mayflower Descendants,” he says. “I am working on research for the Silver Books, which is a project to research and document the first

five generations of Mayflower descendants.”

He is the editor of the George Soule Silver Book and is actively researching seven Pilgrim generations – encompassing about 40,000 people now, including spouses.

Another Mayflower generation

A romanticized, early-20th-century depiction of John and Priscilla Alden’s courtship. The Alden’s marriage, among the first in Plymouth Colony, spurred a work of fiction over 200 years later with American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1858 poem “The Courtship of Myles Standish.” Longfellow, and our own Father Christian Goduti, are both descendants of the Aldens.Father Christian Goduti traces his Pilgrim roots to the Hopkins and Alden families, two of the original 23 families who made the voyage in 1620.

A romanticized, early-20th-century depiction of John and Priscilla Alden’s courtship. The Alden’s marriage, among the first in Plymouth Colony, spurred a work of fiction over 200 years later with American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1858 poem “The Courtship of Myles Standish.” Longfellow, and our own Father Christian Goduti, are both descendants of the Aldens.Father Christian Goduti traces his Pilgrim roots to the Hopkins and Alden families, two of the original 23 families who made the voyage in 1620.

Stephen Hopkins was the only Mayflower passenger known to have previous experience of the New World. In 1609 he had been traveling as an indentured servant to the Jamestown colony in Virginia, but the ship wrecked in Bermuda. Bermuda was a comparative paradise, with plenty of food and water, and many including Hopkins refused to go on to Jamestown, where the fledgling English colony was starving and under attack from local native peoples antagonized by the colonists.

Hopkins led an unsuccessful rebellion and was forced to continue to Jamestown. In 1614, he returned to England to care for his children after his wife died – but only a few short years later, the promise of freedom lured him back to the New World on the Mayflower. This time he had a job as a translator between the settlers and the native tribes, and he brought his children and a second wife, Elizabeth Fisher.

On board the ship, Elizabeth Hopkins gave birth to a son they named Oceanus.Father Christian descends from a sibling, Constance.

Hopkins put his lessons from Jamestown to use in Plymouth – leading efforts to build a peaceful coexistence with the local tribes, serving as a translator, and teaching the Pilgrims how to survive by hunting and farming in their new homeland. Not a member of the Separatists religious group, he ran a tavern and was often in trouble with authorities for violating strict religious bans on drinking and playing games on the Sabbath. Elizabeth Hopkins was notably one of only four women who survived to the “First Thanksgiving.” The couple went on to have five more children in Plymouth, and they both died in 1644.

Father Christian’s other Pilgrim ancestor, John Alden, also was not a Separatist. He was a crewman on the Mayflower – a cooper or barrel-maker. Alden could have returned to

England with the ship, but he signed the Mayflower Compact and chose to stay in Plymouth.

In 1622, he married fellow Mayflower passenger Priscilla Mullins, whose entire family had died during the first winter in the colony. Over 200 years later, Alden and Mullins became famous thanks to a fictionalized account of their relationship and “entanglement with” another Pilgrim named Myles Standish, in a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow titled “The Courtship of Myles Standish.”

Thanks in part to his wife’s inheritance and her connections to Plymouth Colony’s investors, Alden became one of the colony’s most active leaders, elected annually to the Governor’s Council nearly every year from 1640 to 1686. He served as the colony’s treasurer, court deputy, Council of War member, and member of the colony’s trading committee, among other posts.

Along with Standish and other Plymouth colonists, Alden founded the town of Duxbury to the north of Plymouth. He and his wife had 10 children and he died in 1687 at the unusually old age of 89, one of the last surviving Mayflower passengers.

Takeaways from a shared history

According to Father Soule, an estimated 35 million Americans are directly descended from a Mayflower passenger. The Pilgrims’ story of courage, faithfulness and grit is enlightening, he says.

“Some are very famous people but some are not, but all have a part in the story,” he says. “The whole sense of contingency in history has really become clear to me. It strikes me that things didn’t have to work out the way they did. Little things that people who are not necessarily famous did impact the way that things worked out.”F

In reflecting on their shared genealogy and connection to one of the most famous moments in American history, Monsignor Winslow says the most interesting part of the story to him is “less about the fact that we are serving in the same diocese, and more about the fact that we are Catholic priests. Our ancestors were fleeing the Church of England in pursuit of a purer form of Protestantism.

“Now so many of us have made the spiritual pilgrimage back to Rome. Some descendants found their Homeland.”

— Catholic News Herald

The first Thanksgiving Mass in the New World

Thanksgiving honors the pilgrims and Native Americans who came together for a feast in the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts in 1621 to thank God for the abundance of crops.

Yet, did you know that 56 years before Plymouth Rock, on Sept. 8, 1565, the first Thanksgiving Mass was offered in St. Augustine, Florida?

A Spanish fleet landed in the New World and before even unloading the ship or setting up a camp, they offered a Mass of Thanksgiving.

A rustic altar that still stands in the “Nombre de Dios” Mission recalls the Mass offered by Father Francisco López de Mendoza Grajales, diocesan priest and captain of the Spanish fleet. The Mass was attended by the founder of the city, Admiral Don Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, settlers, soldiers, and the native Timucuan people.

A rustic altar that still stands in the “Nombre de Dios” Mission recalls the Mass offered by Father Francisco López de Mendoza Grajales, diocesan priest and captain of the Spanish fleet. The Mass was attended by the founder of the city, Admiral Don Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, settlers, soldiers, and the native Timucuan people.

Historian John Gilmary Shea asserts that the Mass was celebrated “to sanctify the earth and receive the blessings of heaven before taking the first step in building human habitation.”

At the end of the Mass, the Spanish soldiers took off their armor, the Indigenous peoples put down their arrows, and both groups shared food. The Spanish are believed to have contributed garlic stew with pork, chickpeas, and olive oil, and the natives contributed wild turkey, fish, shellfish, squash, beans, and fruit.

Currently in the mission stands the National Sanctuary of the Virgin of La Leche and Good Birth, a devotion brought from Spain in 1603.

According to the local historian Raphael Cosme, “The Spanish Thanksgiving Day tradition continued and spread throughout the missions of Florida, the Carolinas, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana” until 1763, when Spanish residents of St. Augustine left for Cuba and other territories dominated by the Spanish crown.