Editor’s note: In honor of the upcoming feast of St. Francis of Assisi on Oct. 4, we take a closer look at the cross closely associated with this famous saint.

The San Damiano Cross is the one St. Francis was praying before when he received the commission from the Lord to rebuild His Church. All Franciscans cherish his cross as the symbol of their mission from God.

The San Damiano Cross is the one St. Francis was praying before when he received the commission from the Lord to rebuild His Church. All Franciscans cherish his cross as the symbol of their mission from God.

It is an icon cross, meant to teach the meaning of the crucifixion, death, resurrection and ascension of Christ – thereby strengthening the faith of the people at a time when most were illiterate.

The painter is unknown, but the tradition of such crosses began in the Eastern Catholic Church and was transported by monks to the region of Umbria in Italy in the 12th century.

It is painted on walnut. More than likely, it was painted for San Damiano to hang over the altar because the Blessed Sacrament was not reserved in non-parish churches of those times, especially those that had been abandoned and neglected as San Damiano had been.

In 1257 the Poor Clares left San Damiano for San Giorgio and took the San Damiano Cross with them. They carefully kept it for 700 years.

It was placed on public view for the first time in modern times in Holy Week of 1957, over the new altar in San Giorgio’s Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Chiarra (St. Clare) in Assisi, Italy.

An icon is a representation of the living God, and by coming into its presence it becomes a personal encounter with the sacred, through the grace of the Holy Spirit. The San Damiano Cross is then a personal encounter with the transfigured Christ – God made man – inviting us all to take part in it with a lively and lived faith, just as St. Francis did.

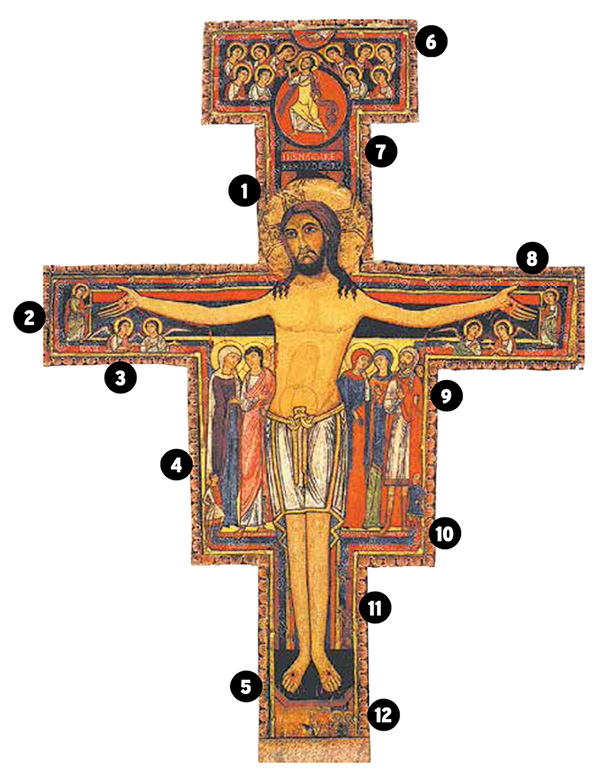

Here’s a closer look at this famous icon:

1. The most striking element of the San Damiano Cross is the figure of Christ. It is not the body of a corpse, but of God Himself, radiating the hope of the Resurrection. He looks directly at us with a compassionate gaze. He does not hang on the cross, but rather seems to be supporting it, standing upright. His hands are not cramped from being nailed to the wood, but rather spread out serenely in an attitude of supplication and blessing. His eyes are open, and He looks out to the world, which He has saved. His vestment is a simple loincloth, a symbol of both High Priest and Victim. He is a figure of light, giving light to the other figures: “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life” (John 8:12). This cross does not express the brute horror of death by crucifixion, but rather the nobility and gentleness of eternal life.

2. Behind Christ’s outstretched arms is His empty tomb, shown as a black rectangle. Christ is alive and standing over the tomb. The gestures of the unknown saints at His hands indicate faith. Could these be Peter and John at the empty tomb? (See John 20:3-9.)

3. Around the crossbar of the cross we see a company of angels, looking in awe upon the Divine Sacrifice. Their hand gestures indicate their animated discussion of this wondrous event.

4. To the left, the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist – “His Mother and the disciple whom He loved” – stand together at the foot of the cross. Mary’s mantle is white, meaning victory (Rev 3:5), purification (Rev 7:14) and good deeds (Rev 19:8). Gems on her mantle refer to the graces of the Holy Spirit. The dark red worn underneath indicate intense love, while the inner dress is purple, symbolizing the Ark of the Covenant (Ex 26:1-4). Mary’s left hand is raised to her cheek – signaling her acceptance and love of John. Her right hand points to John while her eyes proclaim acceptance of Christ’s words, “Woman, behold your son... “ (John 19:26). The blood drips onto John at this moment. John’s mantle is rose color, indicating eternal wisdom, while his tunic is white, indicating purity. His position between Jesus and Mary is fitting for the disciple loved by both. He looks at Mary, “Son, behold your Mother,” but points to Christ.

5. The shape of the cross has changed to enable the artist to include all who participated in the Passion drama. Note that the arms of the cross lift to Christ’s right – indicating that the Good Thief, traditionally called Dismas, went to heaven – while the left hand dips, as the other thief did not. The icon has 33 figures, representing the 33 years of Christ’s earthly life: two Christ figures, one Hand of the Father, five major figures, two smaller figures, 14 angels, two unknown at His hands, one small boy, and six unknown saints at the bottom of the cross. There are also 33 nail heads along the frame, just inside the shells, and seven around the halo.

6. From within the semi-circle at the very top of the icon, He whom no eye has seen reveals Himself, extending His right hand in benediction. His extended fingers symbolize the Holy Spirit, given by the Father to all because of the merits of Christ’s Passion.

7. Above Christ’s head is a portrayal of the Ascension: He emerges from a red circle, holding a golden cross that is now His scepter, as angels welcome Him into heaven. His garments are gold, a symbol of royalty and victory. His red scarf is a sign of His Kingship, exercised in love. IHS are the first three letters of the Greek name for Jesus. The little bracket above indicates it is shorthand. “NAZARE” is “the Nazarene,” “REX” is “king” and “IUDEORUM” is “of the Jews.”

8. Around the cross are various calligraphic scrolls that may signify the mystical vine (From John 15: “I am the vine, you are the branches...”). The seashells symbolize eternity, vast and timeless as the sea.

9. To the right stand St. Mary Magdalene, St. Mary Cleophas (believed to be the mother of James) and the Centurion. The Centurion holds a piece of wood in his left hand, indicating his building of the Synagogue (Luke 7:1-10). The little boy beyond his shoulder is his son healed by Jesus. The three heads behind the boy show “he and his whole household believed” (John 4:45-54). The Centurion extends his thumb and two fingers, a symbol of the Trinity, while his two closed fingers symbolize Christ’s humanity and divinity.

10. In the lower right-hand and left-hand corners are small figures of the Roman soldier Longinus and the Jewish temple guard Stephaton – one holding the lance that pierced the Savior’s side, the other holding a stick with a vinegar-soaked sponge.

11. Near the border of the cross on the right, just below the level of Christ’s knees, is a small rooster. This recalls the denial of St. Peter, who wept bitterly, and reminds us we should not be presumptuous of the strength of our faith. The rooster also proclaims the new dawn of the Risen Christ. At the base of the cross there appears to be a section that looks like a rock, the symbol of the Church.

12. At the very bottom of the cross, the original artist depicts six saints. Their visages were damaged over the centuries and are now unrecognizable. Scholars theorize they are Sts. Damian, Rufinus, Michael, John the Baptist, Peter and Paul – all patrons of churches in the Assisi area. St. Damian was the patron of the church that housed the cross, and St. Rufinus was the patron of Assisi.

— Sources: Father Michael Scanlon, T.O.R., Most Sacred Heart of Jesus Province, USA; www.monasteryicons.com