Feast day: Sept. 29

“Three Archangels with Tobias” by Francesco Botticini, 1470.Each year as the warm days of summer turn to the coolness and bright colors of autumn, the Church celebrates the work and ministry of angels. We begin this celebration on Sept. 29, with the feast of the archangels – Raphael, Michael and Gabriel. The Scriptures speak of how angels are sent to assist in God’s plan of salvation. They are the only angels named in Sacred Scripture, and all three have important roles in the history of salvation. They bring messages and accompany the faithful along the path of daily life.

“Three Archangels with Tobias” by Francesco Botticini, 1470.Each year as the warm days of summer turn to the coolness and bright colors of autumn, the Church celebrates the work and ministry of angels. We begin this celebration on Sept. 29, with the feast of the archangels – Raphael, Michael and Gabriel. The Scriptures speak of how angels are sent to assist in God’s plan of salvation. They are the only angels named in Sacred Scripture, and all three have important roles in the history of salvation. They bring messages and accompany the faithful along the path of daily life.

In celebrating the archangels on Sept. 29, the Church reminds us of three special messengers who were sent to accomplish very specific tasks. The Book of Tobit, one of the classics of the seven apocryphal texts of the Hebrew Bible, tells the story of Raphael, who was sent by God to accompany Tobias in his quest to find medicine to cure the blindness of his father, Tobit. Raphael’s task is to lead, guide and protect his young companion in his quest. Along the way Tobias experiences many adventures, finds love and marriage and, in the end, secures the medicine his father needs. Thus he achieves many goals, receives numerous blessings and completes his mission. This is made possible because of the archangel’s guidance. Raphael has served his purpose well; he has carried out the mission God gave him to accompany, guide and protect Tobias from harm and fight the battles of God.

St. Michael is the “Prince of the Heavenly Host,” the leader of all the angels. His name is Hebrew for “Who is like God?” which was the battle cry of the good angels against Lucifer and his followers when they rebelled against God. He is mentioned four times in the Bible, in Daniel 10 and 12, in the letter of Jude, and in Revelation.

Michael was sent to fight God’s battles. The short letter of St. Jude describes Michael in an argument with Satan over the body of Moses. While Michael does not make any pronouncement against the devil, he does say, “May the Lord rebuke you” (Jude 1:9), indicating the false nature of Satan’s argument. In the apocalyptic Book of Daniel, Michael’s role is much more proactive. He is described as “the great prince, guardian of your people” (12:1). In his vision, Daniel describes the classic confrontation between good and evil at the end of time. Michael is the great champion of the people; he stands ready to greet those who rise from the dead and experience God’s great victory over evil.

The New Testament continues to reveal Michael’s role as a champion for God.

Michael, whose forces cast down Lucifer and the evil spirits into Hell, is invoked for protection against Satan and all evil. In 1899 Pope Leo XIII, having had a prophetic vision of the evil that would be inflicted upon the Church and the world in the 20th century, instituted a prayer asking for Saint Michael’s protection to be said at the end of every Mass.

Christian tradition recognizes four offices of Saint Michael: 1) to fight against Satan, 2) to rescue the souls of the faithful from the power of the enemy, especially at the hour of death, 3) to be the champion of God’s people, and 4) to call away souls from earth and bring them to judgment.

Perhaps the most prominent and best-known of the archangels is Gabriel, the one who delivers special messages to those favored by God. We first hear of Gabriel through St. Luke’s depiction of the Annunciation:

“In the sixth month, the angel Gabriel was sent from God to a town of Galilee called Nazareth, to a virgin betrothed to a man named Joseph, of the house of David, and the virgin’s name was Mary. And coming to her, he said, ‘Hail, favored one! The Lord is with you’” (Luke 1:26-28). Gabriel continued: “Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God. Behold, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son and you shall name him Jesus. He will be great and will be called Son of the Most High and the Lord God will give him the throne of David his father, and he will rule over the house of Jacob forever and of his kingdom there will be no end” (Luke 1:30-33).

Christian tradition suggests that it is he who appeared to St. Joseph and to the shepherds, and also that it was he who “strengthened” Jesus during his agony in the garden of Gethsemane.

St. Raphael’s name means “God has healed” because of his healing of Tobias’ blindness in the Book of Tobit. Tobit is the only book in which he is mentioned, where he speaks: “I am the angel Raphael, one of the seven, who stand before the Lord” (Tob 12:15).

His office is generally accepted by tradition to be that of healing and acts of mercy. Raphael is also identified with the angel in John 5:1-4 who descended upon the pond and bestowed healing powers upon it so that the first to enter it after it moved would be healed of whatever infirmity he was suffering.

— Catholic News Herald Teachingcatholickids.com and catholicnewsagency.com contributed.

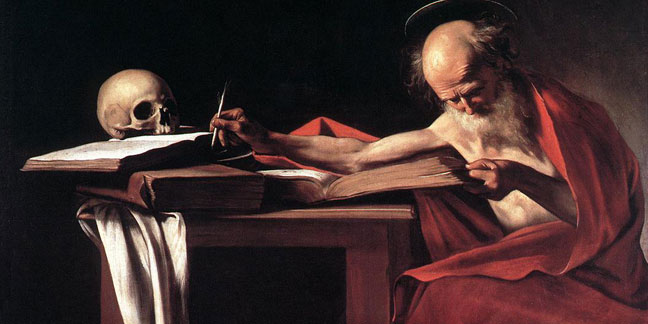

Translated the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into Latin

St. Jerome, the priest, monk and Doctor of the Church renowned for his extraordinary depth of learning and translations of the Bible into Latin know as the Vulgate, is celebrated by the Church with his memorial on Sept. 30.

Besides his contributions as a Father of the Church and patronage of subsequent Catholic scholarship, Jerome is also regarded as a patron of people with difficult personalities – owing to the sometimes extreme approach which he took in articulating his scholarly opinions and the teaching of the Church. He is also notable for his devotion to the ascetic life, and for his insistence on the importance of Hebrew scholarship for Christians.

Born around 340 as Eusebius Hieronymous Sophronius in present-day Croatia, Jerome received Christian instruction from his father, who sent him to Rome for instruction in rhetoric and classical literature. His youth was thus dominated by a struggle between worldly pursuits – which brought him into many types of temptation – and the inclination to a life of faith, a feeling evoked by regular trips to the Roman catacombs with his friends in the city.

Baptized in 360 by Pope Liberius, Jerome traveled widely among the monastic and intellectual centers of the newly Christian empire. Upon returning to the city of his birth, following the end of a local crisis caused by the Arian heresy, he studied theology in the famous schools of Trier and worked closely with two other future saints, Chromatius and Heliodorus, who were outstanding teachers of orthodox theology.

Seeking a life more akin to the first generation of “desert fathers,” Jerome left the Adriatic and traveled east to Syria, visiting several Greek cities of civil and ecclesiastical importance on the way to his real destination: “a wild and stony desert ... to which, through fear or hell, I had voluntarily condemned myself, with no other company but scorpions and wild beasts.”

Jerome’s letters vividly chronicle the temptations and trials he endured during several years as a desert hermit. Nevertheless, after his ordination by the bishop of Antioch, followed by periods of study in Constantinople and service at Rome to Pope Damasus I, Jerome opted permanently for a solitary and ascetic life in the city of Bethlehem from the mid-380s.

Jerome remained engaged both as an arbitrator and disputant of controversies in the Church, and served as a spiritual father to a group of nuns who had become his disciples in Rome. Monks and pilgrims from a wide array of nations and cultures also found their way to his monastery, where he commented that “as many different choirs chant the psalms as there are nations.”

Rejecting pagan literature as a distraction, Jerome undertook to learn Hebrew from a Christian monk who had converted from Judaism. Somewhat unusually for a fourth-century Christian priest, he also studied with Jewish rabbis, striving to maintain the connection between Hebrew language and culture, and the emerging world of Greek and Latin-speaking Christianity. He became a secretary of Pope Damasus, who commissioned the Vulgate from him. Prepared by these ventures, Jerome spent 15 years translating most of the Hebrew Bible into its authoritative Latin version. His harsh temperament and biting criticisms of his intellectual opponents made him many enemies in the Church and in Rome and he was forced to leave the city.

Jerome went to Bethlehem, established a monastery, and lived the rest of his years in study, prayer and ascetcism.

St. Jerome once said, “I interpret as I should, following the command of Christ: ‘Search the Scriptures,’ and ‘Seek and you shall find.’ For if, as Paul says, Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God, and if the man who does not know Scripture does not know the power and wisdom of God, then ignorance of Scriptures is ignorance of Christ.”

After living through both Barbarian invasions of the Roman empire, and a resurgence of riots sparked by doctrinal disputes in the Church, Jerome died in his Bethlehem monastery in 420.

— Catholic News Agency

More online

Learn what a Doctor of the Church is and read more about the Fathers of the Church